By Jack Dulhanty

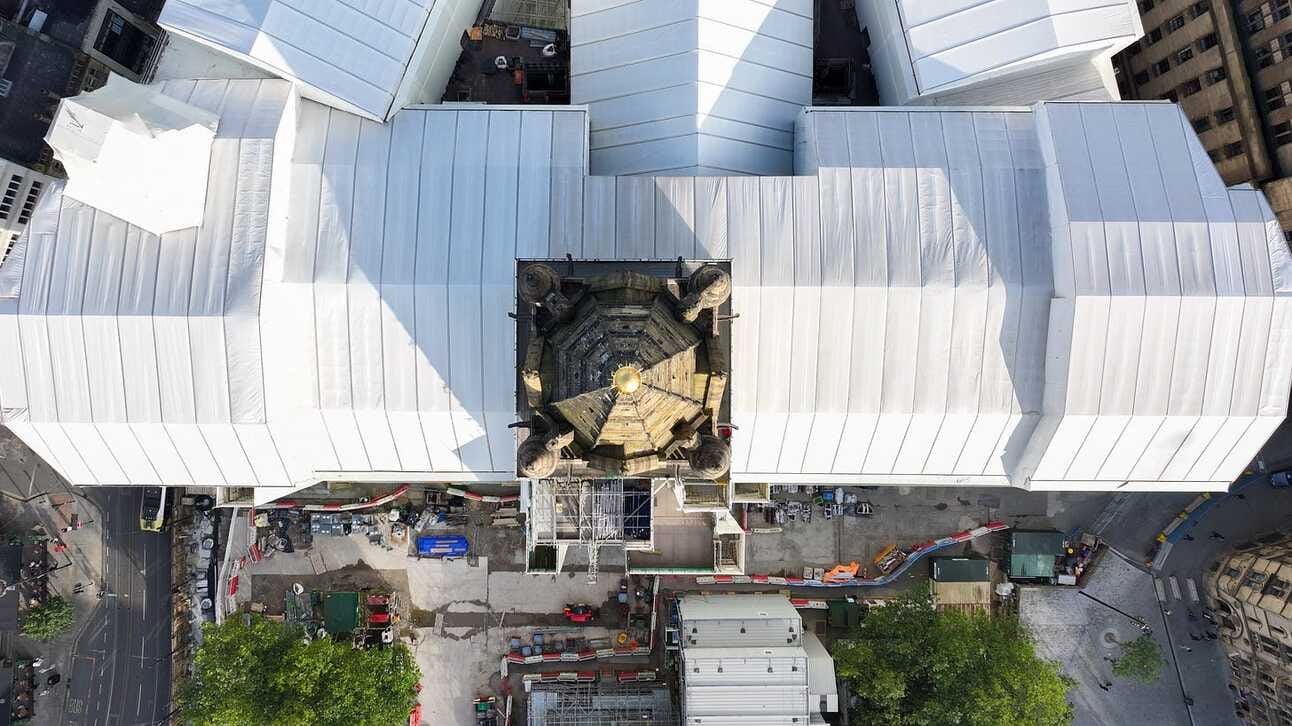

Next to Manchester Town Hall, which is still in the hazmat suit of scaffold and tarpaulin it’s been wearing these last few years, there stands what looks like a pile of shipping containers: these are the Our Town Hall Project offices. Up the stairs that cling to the side of the structure, past the changing rooms, the kitchenette with the cake selection and takeaway menus, the desks with the office workers and the one guy still wearing a hardhat, there is Paul Candelent.

Candelent — tall, lean, ginger beard, wearing a Garmin — is project director for the town hall renovation. Since 2017 (just before the town hall closed but years into the planning process), he has been in charge of the hundreds of specialist contractors, planners, historians, stonemasons, artisans and tradespeople working on the renovation, a project whose sheer scale has no modern precedent. The closest comparison would be to the refurbishment plans for the Houses of Parliament (although those planners have been visiting Candelent’s team for advice).

This small army is eight years into a complex collaboration with the ghosts of the building’s past: not only its original architect, but also every errant handyman, pigeon shooter and occasional crepuscular predator that has left their mark on the building over the last 140 years.

Earlier this week, the project filed an update to the council’s Resource and Scrutiny committee, which laid out how the completion date of the renovation — originally set to be this past summer — was going to be delayed by another two years; it would also require an additional £76m to its already bloated budget. This follows a capital boost last year too, taking the original budget of £325m to £429m.

The reasons for these increases are manifold. First off, the ones you’d expect: the pandemic, inflation, the general complexity of refurbishing any Grade I listed building, much less one of this size and importance. The unexpected reasons are just that: very unexpected.

That’s because, prior to beginning work, the building’s listed status meant there was no way of getting under its skin. Preparatory works were all “desktop surveys”, essentially guys with clipboards squinting up at fixtures and stonework. City centre flight restrictions meant they couldn’t really use drones, so surveyors stood on nearby buildings with binoculars.

Some issues were easy to spot this way: the decades of old and new wiring spilling out of distribution boards like spaghetti, windows bowing, two floors flat out of use. In the end, some 50,000 assets — light fittings, portcullis gates, stained glass — were surveyed and determined to be caput within a few years without renovation. Indeed, within six years, they found the building wouldn't have been safe to occupy at all.

But planners couldn’t spot all the potential work that needed doing this way, and by the time the scaffolding was up, teams were under floorboards and architects face-to-face with masonry, things got a lot more complicated. Since then, the building has revealed more quirks and anomalies with every passing week.

Imagine you’re renovating a Victorian house. You move in, drop your things and look up at the Artex ceiling and the woodchip wallpaper and rightfully decide you don’t want that. So you try and scrape some of it off and — voilà — three layers of plaster come off with it. You realise at that moment you have a different job on your hands, one that is going to take more time and, crucially, more money.

The average person would call this a nightmare, or at least a problem. Candelent and his team, who are dealing with these kinds of issues on a massive scale, have landed on the more euphemistic “discovery”. According to the Resource and Governance report, there has been at least one discovery, sometimes several, every week for the last year. For example, while it was clear the building's roof slates were shot — all 150,000 needed to be replaced — no one had realised the gutters were about to go through as well. Indeed, in the last 12 months, detailing around the guttering has been redesigned 41 times at a cost of £351,000.

Then there was the building’s general structure. “We’ve had significant issues — and this sounds a bit trite,” says Candelent. “But we’ve had significant issues with the building being wonky.” By wonky he means out-of-true, i.e not correctly aligned. This isn’t to say that the building is going to fall over, just that the Victorian architects didn’t always have the same commitment to symmetry as their modern counterparts.

Each one of these new “discoveries” means added time, because the project team has to go back to the drawing board to figure out a new way of working around them. Then they have to go back to Historic England to be sure what they want to do is okay for a listed building, and so on. The building’s wonkiness added two years to the installation of one lift.

But the central issue with the building is how little we still know about it. Designed by Alfred Waterhouse and completed in 1877, there are scant surviving records beyond the original Waterhouse drawings, which were found stuffed in a corner of the basement in 2018. There is no record of the building’s inner works, much less the random bits of upkeep that have been done to it unrecorded over the last 140 years. “Things have been done to the building in the past that don’t seem to have any logic,” Candelent tells me. What’s resulted is a tug-of-war between the current project team and the building’s previous tinkerers.

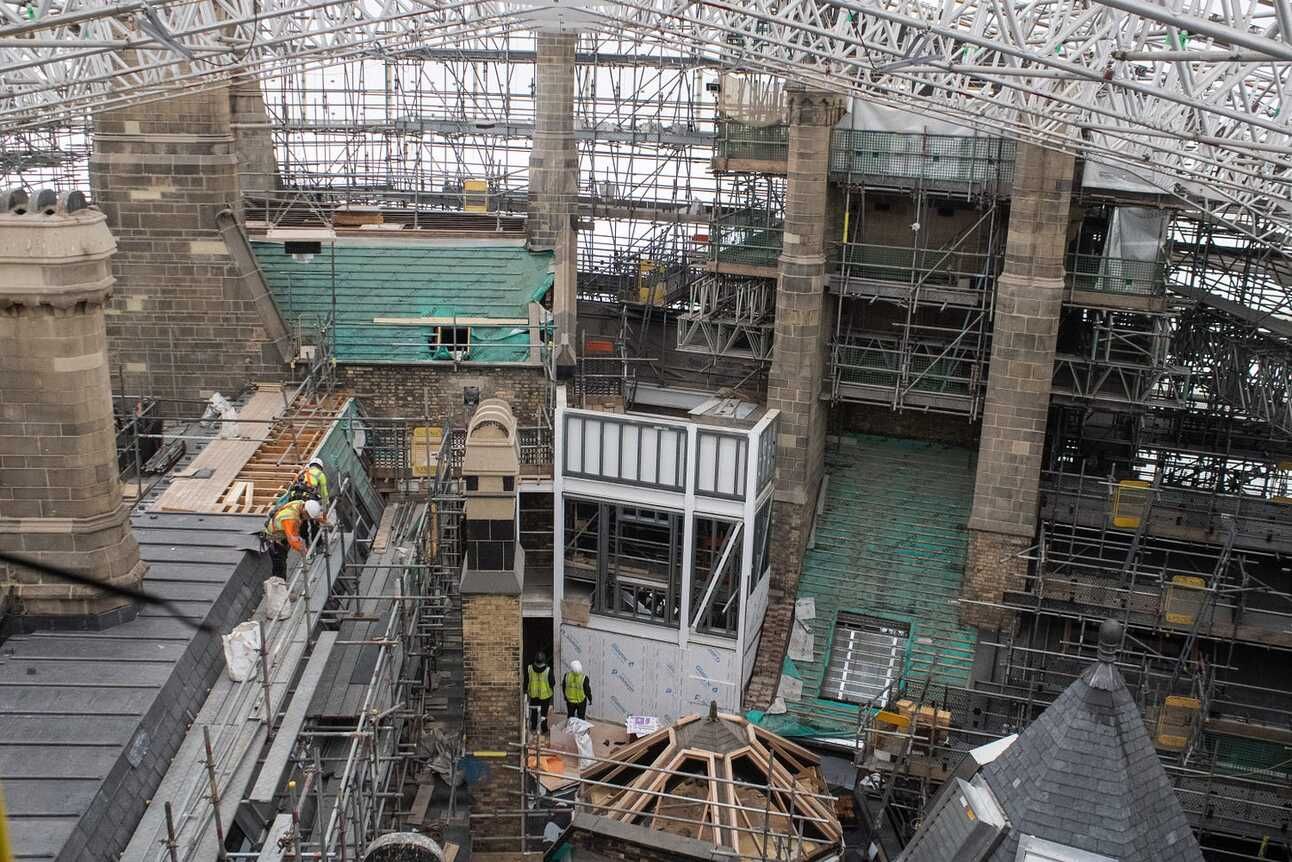

The renovation is now 75% complete. Stepping inside the building feels a bit like stepping into a site of paranormal investigation. There’s tube lighting on tripods to break up the darkness; every inner window is choked black because it's so dense with scaffolding outside.

The fluorescence lights sections of perfectly restored Venetian marble, sourced from the same supplier as the original slabs from the 1800s and broken apart by hand rather than with machines to achieve the same feel. The slate on the roof has been brought from the same quarry in Cumbria that Waterhouse used. There is one wall that will form part of the Great Hall’s cloakroom that has had nothing done to it. Left completely as it was. It is black, with maybe a hint of brown, running up besides the new gleaming surfaces, giving viewers a sense of what the rest of the interior would look like without intervention. It makes its point.

We walk up the spiral staircase to the left of the reception area. Taking the handrail, you can feel a small tube running beneath it that Waterhouse originally installed to supply gas throughout the building. “Waterhouse, by the way, complete genius,” says Candelent. “The way he got services around the building is just incredible, and he’s still surprising us today.”

I’m shown around the building by two project team members, Shabna and Clara. We look at the service “risers” that will eventually carry electricity and plumbing services up the floors via old chimney shafts. These services will also run through the floors, another fruitful site of discovery. In one fairly nondescript room on one of the upper floors, Candelent lifts a floorboard up and shows me a steel beam. Everywhere else in the building, you would expect a timber joist, but at some point over the last century and a half, someone decided a steel beam would work better.

The beam happens to block the route of one of the service lines, meaning the team will now have to go back to the drawing board to see how they can get around it. These kinds of discoveries elsewhere in the building — for instance, one gas trench that ran through the floor and could have carried electrical lines, but was for some reason filled with concrete — means the team has to wire or plumb up around a room’s ceilings and walls. Essentially, they need to find a way to make everything work without damaging the heritage of the building. This leaves the team in a continuous phase of construction and redesign for months on end.

Frequent pauses in the work means that contractors have had to stand down while solutions are sought. When this happens, the contractors can claim against the project for having to delay their work; so far they’ve logged some £50m worth of contractors’ claims for lost hours, a spokesperson tells me. But, they say, there is a “process of ongoing robust negotiation” towards lowering that figure.

At one point in my conversation with Candelent, I ask whether there have been any nice discoveries and he laughs. Not everything they’ve found has meant more time and money. There has been old caps and boots under floorboards, perfectly preserved cigarette cards, beer bottles up in the attic. “You can imagine back in the day, maybe the ‘30s” says Candelent. “Workers at lunchtime, a nice sunny day in Manchester, go and sunbathe on the roof, get a bottle of beer out.”When excavating one of the load bearing walls, the team also discovered a brick printed with the paw of what looks like a kind of predator, perhaps a wolf. During the original construction, there was a furnace making bricks to order; whatever the animal was, it’s presumed to have walked onto one while it was cooling.

I myself had never set foot in the Town Hall until earlier this week. Never really had much interest in it until it was closed to the public. So I can’t really speak to how much nicer the place seems compared to previously; I never saw it when the wallpaper was peeling and the roof was leaking. But I do know that in the Great Hall, the frescoes on its vault have been restored, and even with the minimal lighting seem to glow. (There were a few air gun pellets lodged up there, though they didn’t take away from the frescos’ magnificence; theories on the pellets include past attempts to take down pigeons, or maybe celebratory balloons.)

All the statues have been wrapped in white blankets which make them look kind of like corpses pulled from a mafioso’s boot and propped up against the wall. A black void hums where the organ used to be. Beneath the floorboards the team have been finding packed sawdust that must have been used to dull the sound of the organ due to complaints from neighbours. I suppose the council has never been in the business of serving itself noise abatement notices.

When the renovation is completed, the building will be beautiful. Anyone would be bold to argue against that. Whether it will feel worth nigh-on half a billion pounds — more money could still be requested — will be a whole other source of debate. But one thing that is for sure is that the town hall will be more open, and have more of a presence, than it ever has. Beyond housing council staff, three coroner’s courts (currently in the Royal Exchange), and hosting weddings, there will also be a whole visitor experience, exhibitions of objects found in the building and presentations on its heritage, even tours of the clock tower.

“There are 16 steps from Albert Square into the landing in the building,” Candelent says. “And in all the old [Victorian] photographs you see of the great and the good talking to the masses, they are up here, and it is the heads of the riff raff down there somewhere. We want to reverse that. A People’s palace, I suppose — if that doesn’t sound too corny.”