Let me take you back to the end of the 1980s. I was in the final year at my Wigan secondary school, doing a week of work experience at the Wigan Observer. I had nurtured a fancy to be a journalist since watching All The President’s Men on TV the year before and The Obbie - as it was known locally - agreed to have me in.

It felt like I had stepped into Narnia. I was sat down next to actual local celebrities, journalists such as Richard Bean and Geoffrey Shryhane. The place was never quiet - there were people on the phones, doing interviews and scrawling rapid shorthand notes. There were debates about sport and politics and who sold the best pies. There were news conferences and cups of tea and the clack-clack-clack of keyboards.

Join The Mill now to get our quality reporting about Greater Manchester in your inbox every week

The editorial team was about 15-strong and that was on a weekly paper in a town that also had a daily, the Wigan Evening Post, a weekly free-sheet (fully staffed with journalists), the Wigan Reporter, and coverage from both the Manchester Evening News and the Liverpool Echo, at opposite ends of the borough.

Three years later, I walked into another newsroom, this time that of the Chorley Guardian as a paid employee, and embarked upon a career in local newspapers that would last 26 years. Within a year I was working at the Lancashire Evening Post in Preston, where there were journalists as far as the eye could see - 20 reporters, just in the head office, with more in district offices in Lancaster, Southport, Chorley and Leyland.

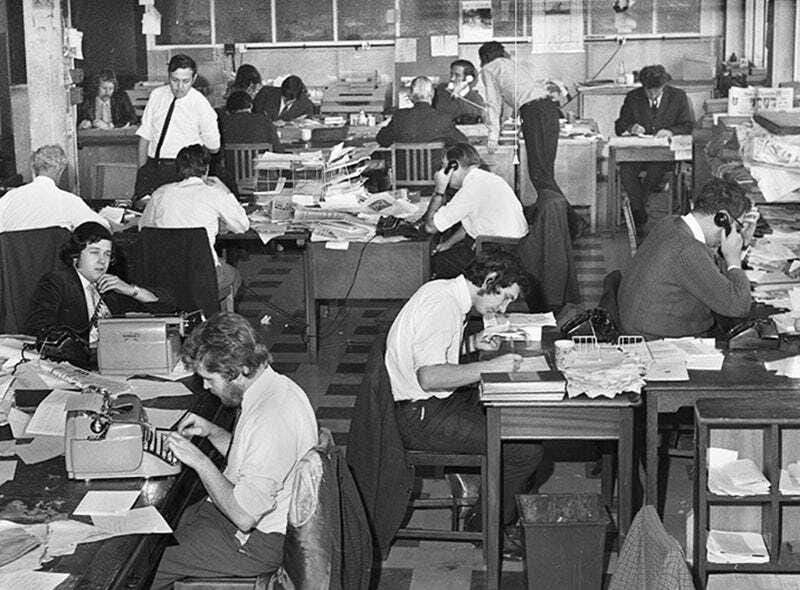

The (big) staff of the Lancashire Evening Post in 1998. That’s me front left with a goatee.

There were banks of sub-editors. A command desk of news editors, assistant editors, and deputies. Revise desks. Picture desks. Photographers. Feature writers. A huge sports team. And a pod of six or seven newsdesk secretaries, copy takers and archivists - in fact, more of them than there are journalists in most local newsrooms now.

Unlike Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford in All The President’s Men, I never broke a Watergate of my own. But I did work during what might have been the last gasp of local journalism as a serious force to be reckoned with. Working for a local paper really felt like the best game in town.

In the days before Facebook and NextDoor, your local paper was the only way to find out what was going on around you. The nationals didn't care about Wigan, or Warrington, or Bury or Blackpool unless there was a particularly juicy murder there. If you lived in Manchester or Liverpool you could expect to read about your local football team in your morning daily, but for everyone else… well, who was going to tell you who was on the bench at Spotfield Stadium on a wet Saturday afternoon in November apart from the local rag?

The Mill publishes intelligent, balanced journalism about stories in Greater Manchester, from politics to culture, business to crime. Join our mailing list for free to get weekly stories in your inbox, or become a paying member to get The Mill Daily.

And then, around the turn of the millennium, the unthinkable happened. Local newspapers entered an extinction phase.

When I sat my journalism exams in 1989 I did so on a manual typewriter. When I started at The Chorley Guardian, they had just got computers. There was no network, so you wrote a story on your desktop PC, saved it to a floppy disk, then had to take it over to the newsdesk secretary - who had to stop what she was doing, download your story on to her PC, and send it to the news editor.

People still called the advent of computers “The New Technology” in 1989. I was 19 and embraced it. The old stagers who smoked in the newsrooms and tipped ash into their desk drawers were more suspicious. What no-one said - because no-one knew - was that it was a technology that would kill the job stone dead.

It was, of course, the internet what done it. When it arrived in the mid-90s, when I worked at the Lancashire Evening Post, the internet was eyed warily by the local press. At first, we thought it was going to be a useful research tool, especially with email bolted on. No-one thought that the internet would ever actually replace physical newspapers.

When you are working in an operation as busy and well-staffed as we were, you had every reason to feel confident. When I later became news editor, I had reporters assigned to magistrates’ courts, crown courts, inquests, council meetings, health meetings, police press conferences, and any one-off events on the diary. That left a team of reporters in the office who would generate their own stories, call the emergency services every hour, on the hour, and respond to breaking news. Some mornings there would be fleets of cars (old bangers, of course) pouring out of the car park.

When it was first mooted that newspapers could actually have a presence online, I remember one old hack pointing at the big, beige monitor, keyboard, mouse, and system tower on his desk and quipping: “Well, I’m hardly going to take this lot into the bogs every morning for a quick read, am I?”

The MEN’s website in 1998, then called Manchester Online. Michael Owen was still a precocious youngster and the paper still had extensive classified ads.

We had one mobile phone in the entire organisation at that point. It was about two feet long and had to be connected to a battery as big as a rucksack, and worn like one. It was like something from M*A*S*H*. If the idea that putting stories on a website seemed alien, the thought of people reading those stories on a mobile phone was pure science fiction.

Looking back, though, it wasn’t actually people moving to reading news online that devastated the newspapers. It was all the other sites that suddenly sprung up online alongside them. Sites that very rapidly started stealing a market that newspapers had monopolised for decades: local advertising.

The three pillars of local newspaper advertising were always jobs, cars and homes. That’s why on certain nights your local paper was as thick as a telephone book (if you remember those), with huge sections on recruitment, houses and motor sales. And what the internet gave those businesses was much better advertising options than newspapers could offer - more targeted and more automated and cheaper.

Now you could sell your car on Auto Trader. Estate agents could advertise on Google - to people who were right at that moment searching for a new house. Specialist job sites started popping up. Almost overnight, the three main cash cows that kept local newspapers afloat were being milked by a new breed of dot com entrepreneurs.

An ad rep sells space in The Wigan Evening Post and Chronicle in 1971

I can remember the meetings where the advertising managers reported that one car dealership or estate agent had stopped advertising and decided to move their business online. Then the next week there would be another. Soon, thick pull-out sections stuffed with houses or cars or jobs - mighty revenue drivers for newspapers, which subsidised an incredible amount of local journalism - had shrunk down to a couple of pages at the back of the paper.

And as revenues plummeted, the media companies embarked on - to coin a phrase you don’t often see outside of local newspaper stories themselves - swingeing cuts. Year after year, editorial departments have been eviscerated up and down the country.

Back in the 1990s, the Manchester Evening News had around 130 journalists, according to a former editor there. Now there are about a third that number - around 45 journalists employed by MEN and an additional six “Local Democracy Reporters” paid for by the BBC through the license fee to cover things like local council meetings.

When I started at the Chorley Guardian there was an editor, a deputy editor, a news editor, a chief sub, two other subs, a newsdesk assistant, two sports reporters and four reporters. Now the paper is run from Preston and lists one “Chorley reporter”.

The Mill publishes intelligent, balanced journalism about stories in Greater Manchester, from politics to culture, business to crime. Join our mailing list for free to get weekly stories in your inbox, or become a paying member to get The Mill Daily.

Its editor is in fact “Group Editor” for not just the Chorley Guardian but the Lytham St Annes Express, the Fleetwood Weekly News, the Leyland Guardian, the Garstang Courier and the Longridge News. And she’s also the deputy editor of the Lancashire Evening Post. All of those papers used to have their own editors when I started out.

Inevitably, two decades of deep staffing cuts and endless reorganisation of once-proud newspapers into regional hubs has had a major effect on quality. I follow a lot of local newspaper Twitter accounts and the other day half a dozen tweets dropped in together. Of those six stories, only one had any relevance to the geographical patch the newspaper covered. The rest were national stories. One was about when Greggs would start selling Christmas-flavoured pastries.

Newsquest, the owner of a string of newspapers across the north, including the Warrington Guardian and Bolton News, recently instituted targets for individual reporters to reach based on how many clicks their stories get online. It doesn’t matter what those stories are - they don’t have to be local.

Unlike the print ads we lost, most of the online ads are not local - they are supplied by vast programmatic “exchanges” that put the same ads on the MEN as they put on the Mail Online. So there is less incentive to build up a loyal local audience, and plenty of reason to pile up web traffic no matter where it comes from. If a viral story with a clickbait headline about Manchester United generates 50,000 clicks around the country or even around the world, that’s worth publishing.

It was also clear pretty early on in the development of news on the internet that online advertising created perverse incentives - that in order to drive revenue you needed to pump out ungodly volumes of content, volumes that turned talented, idealistic journalists into “churnalists.” The warning signs were there, but instead of maintaining the quality of their product and pivoting to subscriptions, newspaper executives carried on with an ads-based strategy, trying to beat the internet at its own game.

Most local newspapers are now owned by a handful of massive media companies, among them the American-owned Newsquest (Bolton News, Lancashire Telegraph, the Warrington Guardian), the Daily Mirror’s owner Reach Plc (the Manchester Evening News, the Liverpool Echo), and JPI Media (the Lancashire Evening Post, the Yorkshire Post). All make the vast majority of their revenue from advertising, and only now - after cutting back staff and quality for two decades - are they making a serious attempt to sell subscriptions.

The busy newsroom of The Wigan Evening Post and Chronicle in 1971

I took redundancy from my last local paper, Bradford’s Telegraph and Argus, five years ago. These days I write books and contribute features and reviews for The Guardian and The Independent as a freelancer. I miss the bustling offices of the newspapers I used to work for, and it saddens me that they aren’t bustling anymore.

Why should anyone care about any of this? Because local newspapers are accountable, and they hold people to account. They are largely politically independent. They are staffed by dedicated people, albeit in dwindling numbers. And, unlike the news you get from Facebook, or Nextdoor, your local newspaper’s news is safe and verifiable and most definitely not the work of Russian bots.

If this all sounds bleak, it really is. But only because the newspaper owners are playing the wrong game. And if someone starts playing the right game, and playing it well, there could still be a future for local journalism. Nextdoor and Facebook local groups show there is an appetite for local news. It’s obvious. Of course, people want to know what is going on in their communities.

Perhaps when the newspaper groups that have driven our venerable North West titles into the ground, some enterprising individual will pick them up for a pittance and reboot them. Maybe the people running local newspapers will finally realise that online ads have led them down a blind alley, and will reverse course.

Who knows. I won’t turn this piece into a plug for The Mill, but please take my career in newspapers as evidence of one of thing: if we don’t do things differently - if we don’t back new approaches and new models and new ideas - pretty soon there will be nothing even faintly resembling real local journalism left.

To get high-quality local journalism about Greater Manchester in your inbox, sign up to The Mill’s free mailing list using the button below, or join us as a paying member.

Click here to find out more about The Mill — Greater Manchester’s new quality newspaper, delivered via email.